For the past few weeks, I’ve been tucked away at the Hedgebrook Writers’ Residency—writing, painting, and resting in the woods of Whidbey Island, almost entirely offline.

Today’s newsletter was written before I left, on October 6th. It’s full of time stamps, but it felt more honest to let it remain slightly outdated than to edit the timeline and pretend it was written here, now.

Since then, I am somewhere (and someone) entirely new. Still, I wanted to share it as it was. As I was.

It has now been one hundred days since Andrea died.

I miss them always.

***

October 6th, 2025.

It’s been eighty-four days since Andrea died, and I’m realizing I no longer know how months work. If Andrea took their final breath on July 14—somewhere in the lacuna between Sunday and Monday—does today, twelve weeks later, count as three months? Or do I wait until October 14th to mark this anniversary I never asked for?

Grief runs on multiple clocks.

By the lunar calendar, it’s been three moon cycles. Three revolutions of illumination, of halving, of darkness. A celestial measure feels right—a nod to Andrea’s favorite muse. But the 14th is easier to mark.

And don’t I deserve grief to be easier?

If I keep the metronome of my loss by the beat of the 14th, then Valentine’s Day will be seven months.

That won’t be easy at all.

Twelve weeks in, and reality begins to take on a new texture. Some say the shock is wearing off, but what I feel now is more shocking than anything before. To accept that I won’t see Andrea, framed by a door. Obliterating.

You’re not coming back, are you? I whimper. A dog abandoned in a shelter. I can’t believe it. And so I hear myself tagging the word alleged onto death. As if Andrea’s heartbeat going quiet beneath my hands was a rumor, a hoax, a disappearing act.

Proof of magic.

Since Andrea’s alleged death, three moons ago, I’ve done four talk-backs following screenings of Come See Me in the Good Light. Before the first one (the hardest one) in NYC, our director Ryan White asked if there was anything I wanted the moderator to address.

Preparing for this sort of thing is not my preference. The honesty that arises in the moment, the absence of script—that’s when I find myself most articulate, most true. When interviewed about drowning, I think it’s best to answer from the tumult of the sea, not the safety of a shoreline.

“No,” I said to Ryan, sipping my mint tea. “But I can think of one thing I don’t want him to ask.”

It isn’t what you think. I’m not afraid of anything getting too dark, too personal, too close to the bone.

The opposite is what scares me.

“Just don’t let anybody ask, How are you?” I said, as I watched Ryan strike a phrase from his own mind.

You might be wondering, What’s wrong with “How are you?”

First, there’s the issue of logistics. Am I supposed to answer from this exact moment? If so, the honest reply might be: a little hungry. Somehow I doubt that’s what anyone is asking about—the tawdry desires of a body still living.

Do they mean this week? This month? Since we last spoke? Since Andrea went missing from matter? As if grief were a fixed state, a stasis. As if a few flimsy adjectives could hold it.

Listen—I revere language. When someone says, “There are no words,” I think: try anyway. Find them. Here we are together, at the lightless bottom of the well. Don’t tell me there’s no rope when your eyes haven’t yet adjusted to the dark. Reach, fumble, grab onto something. Anything.

Okay. Maybe we’re not in the same well. But you’ve been in your own pit of grief, and so perhaps you agree: slightly better than no words are the two people always seem to send the bereaved: Love and Light.

I know the intentions are good. But where does all that love and light go? I’ve been sent it, but I’ve never once received it. Does it get intercepted mid-air? Hijacked by HomeGoods and stitched onto a decorative pillow, haphazardly tossed into a discount bin?

Would it be possible to exchange it for something not written in invisible ink? At the bottom of this daily obituary—this constant announcement of my love’s truncated life—could I write: In lieu of love and light, send flowers. Something gorgeous I know will die, so I can stay in the practice. So I won’t be so surprised again.

Better yet, in lieu of love and light, send a time machine. Let me have one more day.

My god. What would the two of us do with one more glorious day?

I don’t mean to sound ungrateful. I’m not. I appreciate every heart that is brave enough to stumble in my direction. It isn’t common to console a thirty-seven-year-old widow. No language feels right, because nothing about this is right. The divine order has slipped its axis.

And of course, “How are you?” is not an unkind question. Not at all.

But it is a thimble at the mouth of the river. It’s too small. The answers won’t fit. So when I’m asked, I default to: “I’m a lot of things…” Which is true—but not true enough.

Not for the kind of conversation I want to have in this life.

Not for someone who believes in language professionally, biblically.

As if the next word is a rope that might pull us out of the bottom.

As a writer—and a writing teacher—I’m always telling my students: show, don’t tell. So perhaps, instead of that feeble salutation, we should say to those in the trenches of loss: show me three images from your life right now. Three snapshots that at least graze the magnitude of all that you are carrying.

Now that I can do:

Last week, I went to World Market to buy candles. It was the first time I’d been there without Andrea. World Market was their favorite store. Together, we were throw-blanket hoarders, pathological redecorators.

After the pandemic hit and when the health protocols stretched longer for us than anyone else we knew, rearranging the furniture or papering a new accent wall was a way to trick us into believing we were seeing new places. Traveling. The two of us repainted our living room so many times I swear it brought us a quarter-inch closer together. We liked that. Closeness.

I didn’t recognize the store without Andrea walking through it. Running their small hands along furry footstools, spinning around in the velour desk chairs like a kid. The store felt suddenly foreign. Cubist. It no longer made sense. As if Andrea was more integral to its structure than the beams that kept it upright.

I purchased two candles. One cedar, one pine. Andrea was allergic, so we never kept them in our home. Sometimes I try to look for the tiny concessions of such a tragic loss: Now I have candles!

Back at home, I struck a match and ignited the new white wick, watched as a tiny flame tried to dance. Then I worried Andrea doesn’t know that spirits don’t have histamine responses, and would feel somehow unwelcome among the fire, the fragrance.

I blew them out.

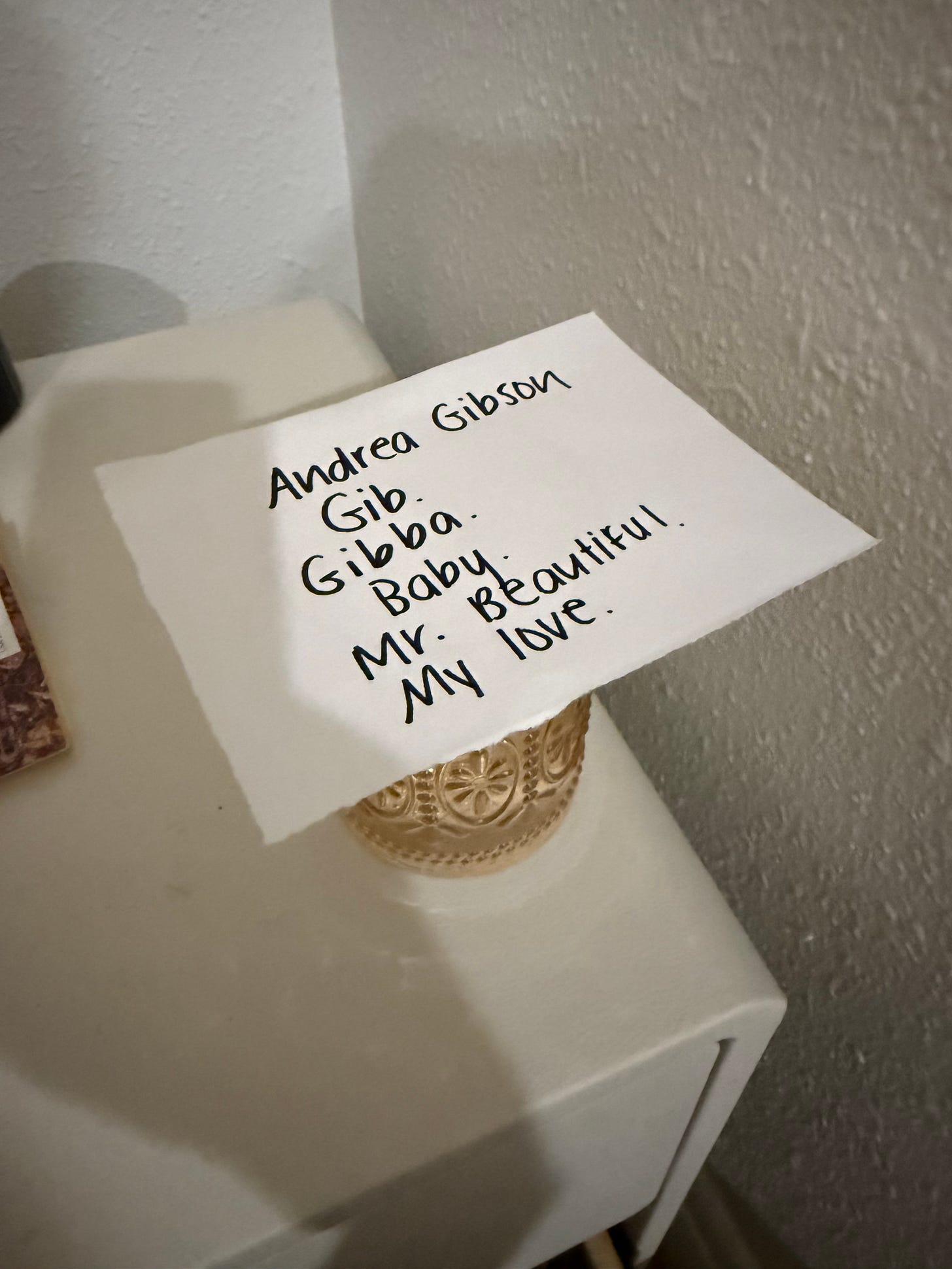

I wrote Andrea’s name on a piece of paper and placed it on top of a glass of water on my nightstand before bed. A medium on Instagram said that was how to get the dead to visit you in dreams. I wrote every name I had ever called them on the paper, leaving no stone unturned. Andrea. Gib. Gibba. Baby. My love. Mr Beautiful.

I want to be someone who says, “The veil is thin,” and knows exactly how to touch Andrea across it.

I dreamed, instead, of a clogged toilet.

Perhaps my mind was telling me that social media psychics are full of shit.Life goes on. A TV show that never resolved in Andrea’s lifetime airs a new season. The plot continues, the protagonist finds a loophole in death and we all exhale. There will be a new storyline soon.

A Taylor Swift album takes over the airwaves and I’ll never see Andrea dance to it, unembarrassed, or write their own lyrics in the margins between the bridge and chorus.

My timeline floods with Taylor. In an interview, she gushes about Travis. On her ring finger, a blinding rock. She says something both funny and lovely, about how large her fiancé is. How broad his shoulders. She says that seeing him walk through a door is “genuinely a privilege.”

She has no idea. I want to see Andrea walk through a door. I would trade anything for one creaky hinge.

Instead, I open the freezer, hoping Andrea left a secret note in there on a lucid day when they were anticipating my inevitable loneliness. I’ve scoured winter coat pockets, glove compartments, the backs of paintings for one more scrap of Andrea. One more love letter.

What I find instead is a gluten-free, zero-net-carb pizza crust.

It was so important for Andrea to eat healthily throughout cancer. Even in their last week of life, Andrea was still refusing sugar.

God, we were hopeful. God, we were so naive.

Sometimes what buries us isn’t the graveyard, but the freezer aisle. The pop star.

So. How am I?

I find myself sometimes, on the kitchen floor, crying.

I find myself sometimes, in the morning light, dancing.

The moon never changes. It’s only us, turning, who call it half or full.

I take a breath. Andrea would want me to have candles, I think, as I lower a match to the blackened wicks, and the house fills with the scent of forests.

As I write their name, again, on a piece of paper, place it atop a glass of water, and will myself to dream.Love & [candle] Light,

Meg [+ Andrea, forever].PS. Here’s a video of our biggest decorating fail:

This: "The moon never changes. It’s only us, turning, who call it half or full."

Wow.

I was struck by what you said about dreaming of a clogged toilet. I have recurring dreams of rooms full of clogged toilets and needing to use one.

Both my wife and our dog are currently dealing with cancer. And of course me. My wife’s breast cancer was caught early through a routine mammogram and is being surgically removed next week. Andie’s mass found on her lung (much larger than Jayne’s) is being evaluated again today for a second opinion by a vet oncologist. Lung lobe surgery has been recommended.

Along with “how are you”, “have a happy day” feels off to me in the midst of this situation. The most important thing right now is to be in the company of others who care enough to be real. I appreciate your sharing very much.

We have a 34 year old daughter who is coming to be with us next week. Can’t wait to see her.