Sweet Community,

Two and a half weeks have passed since I last wrote, and I’ve missed this sacred space we’re building together. I’ve been on the road with the documentary—three screenings in three states.

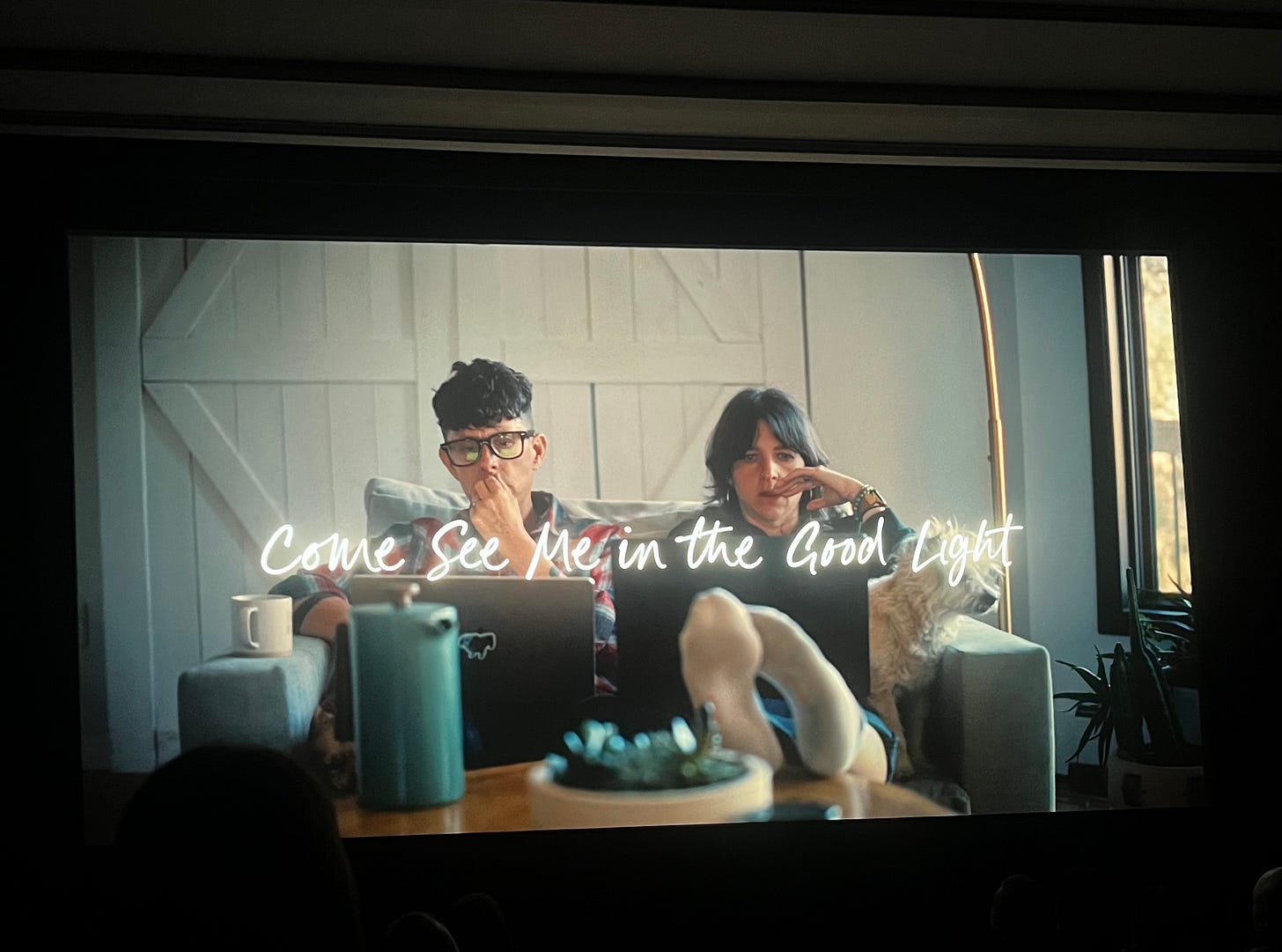

If you’re new here, or didn’t yet know, there is a documentary about Andrea and me, titled Come See Me in the Good Light. It stunned us by winning Sundance’s Festival Favorite Award and is still circling cities worldwide. Soon, on November 14th, it will stream on AppleTV+ so anyone, anywhere, can see it.1

Though Andrea originally imagined the crew would ultimately document their death, our director Ryan White says that after spending just a few days in our presence, he realized it would not be a film about dying—but about living.

That the film was completed so quickly was itself a tremendous act of love. After only one magnificent year of shooting, Andrea and I were given the rarest gift: to sit beside each other, hands threaded for ninety minutes, watching the surprisingly joyous life we tried (and failed) to capture in words articulated so precisely on screen.

As the credits rolled at Sundance, Andrea kissed my wet cheeks and whispered, “This is going to help so many people.” To them, that was the highest prize art could achieve. Andrea was never concerned with what they could get from their work—but what they could give.

Last week’s screening in NYC was the first time I saw the film without Andrea in the world. In the first few minutes, I could hardly pick my head up. The scenes hadn’t changed, but I had—every moment refracted through the jagged lens of grief. My heart broke like a bowl thrown at a wall. I cried the whole way through.

Like a widow who tries to dive into her lover’s casket, I wanted to plunge myself into the screen, into the past, into a version of our home where Andrea still wandered, still sat at our desk to type out some casual brilliance.

My hand felt operated by a delusional marionette. For an hour and a half I suppressed what felt like the most natural urge: to reach toward the film and pluck Andrea out of it, back into this tangible reality, into the red velvet seat beside me.

Sitting there with the projector’s soft whirr in the distance, the faint stick of soda beneath my shoes, my lap a receptacle for tattered Kleenex—I was reminded of the first movie that ever undid me in the dark: Titanic.

It was the winter of 1997. I was nine. The movie was three hours and fifteen minutes long, but my attention never wavered. I wonder if I even blinked.

What’s been classified as “an epic romantic disaster film” was an instant classic in my fourth-grade heart. At that age, I hadn’t yet loved. I hadn’t yet lost. But something in me needed those swells of human emotion, as if my body understood before my mind that they’d be important one day.

(Maybe that’s what all storytelling is for. To let us practice being human before life requires it. We don’t just watch movies and plays, we don’t just read books; we try them on. And when reality finally arrives, we recognize the shape of it. Our hearts have already practiced.)

As I studied Jack and Rose—their ungovernable romance cut tragically short—I sobbed so hard that a woman in the row behind us tapped my mother and said, “Perhaps you should take her out of the theater.”

Without pulling my gaze from the unfolding wreck, I hissed at her demonically. “NO!”

My No conveyed the immutable facts: she would have to drag me down the aisle, kicking and screaming, to pull me away from whatever holy thing I was witnessing.

What can I say? I was a dramatic child.

As the first Halloween after Andrea’s diagnosis approached, I asked if they’d dress up as the Jack to my Rose. I already had The Heart of the Ocean necklace, which I’d decades ago begged my father to buy for me from the kiosk in the mall behind our house, where it was just $39.99. Years later, it was the first gift I ever gave Andrea. Plastic sapphire, rhinestone frame. I wanted to offer them my heart in every way a person could.

Halloween had never been a high holy holiday to Andrea—probably they thought forty-five was a little old for costumes. But they wanted to make me happy. So they slipped on suspenders, a white henley, a heartthrob blond 90’s haircut. My pre-teen dream.

Later, Andrea wrote:

When I call cancer, “The Big Sea,”

[Meg] is the only one who knows

I mean the Big Ocean

where we met our own Titanic

and didn’t sink.

She even convinced me

to dress up as Jack and Rose

for Halloween.

Though my baldness was in no position

to pass up the opportunity to wear a wig,

I was a bit nervous to play the part

of the guy who dies.

But I wasn’t really Jack, was I?

I was Rose.

And her heart was the door

that opened so wide it flew

off its hinges and kept me afloat.”

Until recently, I would have said, without irony, that Titanic was my desert-island film. (Close seconds are Moonlight and Little Miss Sunshine. My three-year-old self wants me to advocate for The Little Mermaid—I suppose I love a romance at sea.)

Now, of course, I have a different answer: Come See Me in the Good Light. Because what more would I want to watch, again and again, than my love’s face rendered six feet tall (as tall as it is in my mind?) To hear them laugh again, in surround sound?

To rewatch my own epic romance (disaster) film?

That night in New York, immersed in that cinematic smell of popcorn and cherry coke, as new tissue packs appeared for me from the hands of strangers, someone lovingly suggested, “If it’s too hard, you don’t have to stay.”

But let me tell you something about me: I will never leave the theater.

These feelings are not something I want to run from, but toward.

To be devastated in the dark reminds me I’m alive in the light.

And because I allowed myself to unravel into a mess of tears and tissues in the very public Roxy Cinema of Tribeca, let me tell you what happened after: Joy.

The next day, someone caught me on video with a literal skip in my step. For a minute there, I was scared to share that. Scared that people would only recognize the magnitude of my love if I was in a constant state of shipwreck. Only if I was sunk to the very bottom.

But Andrea named my open heart as the thing that buoyed us through their diagnosis. And now, it’s what keeps me above water in their absence.

In dipping my toes into mediums and spirit-channeling, I’ve learned that an open heart makes it easier for those on the other side to reach us. And there is nothing I want more than to believe Andrea and I can keep our conversations going, keep flirting across the realms.

Maybe that’s why I was able to be a conduit for the following bit of magic:

On the day after the NYC screening, we headed to LaGuardia Airport to make our flight to Portland, Maine, for a showing that evening in Camden. A middle-aged man with a Jamaican accent was soliciting me to sign up for TSA CLEAR/PRE-CHECK. Because I’ll be traveling quite a bit in the upcoming months, Ryan & Jessica (producer) encouraged me to enroll.

The man kept calling me, “Young Lady,” then apologizing for it.

“Why are you apologizing?” I asked. “It’s better than ‘Old Lady.’”

At this, he squared his shoulders toward me, looked me in the eye with a staggering intensity. “You are not an old lady. Listen to me. You are going to live eighty more years.”

“Eighty?” I did some mental math and laughed, not sure I even wanted to be one-hundred-and-seventeen.

“Yes,” he said, sternly. “You are going to be like Rose.”

Believe it or not, I didn’t get the reference.

He continued. “Rose. From that movie Titanic.”

I looked to Ryan and Jess. All of us were stunned.

“You are going to outlive everyone you love,” he continued. “But you are going to live a beautiful life.”

There are probably rules against hugging a TSA Agent, but I couldn’t help it. I threw my arms around him. This man, a vessel, I believe, through which Andrea visited me once more.

Hi baby.

***

A final note: in the late ’90s, when I got Titanic on VHS, it was so long it came in two tapes. The first tape could almost pass for a rom-com: two people from different worlds meet on a majestic ship. If you wanted to, you could stop there. End on a kiss.

But the second tape is inevitable—the ending we all knew from the beginning. The infamous sinking. Whether we watch it or not, it happens. The iceberg is already in the water.

It’s all going to end. That’s what makes it beautiful. Don’t skip the sadness. Don’t leave the theatre. Keep your eyes open. Keep your heart open. If it’s all going down anyway, listen for the violins.

Love,

Meg [+ Andrea, always].

A bit more on Come See Me in the Good Light: Both Andrea and I have never been so excited to share art we’ve made. Both of us hoped that people would see it in theaters, specifically. Why? A theater is a cathedral of strangers where what would have been private becomes collective. The handful of times Andrea and I saw the movie in actual cinemas, we marveled at how laughter multiplies. How one person’s joy catches fire in another’s chest. How one person’s sob reminds the rest of us it’s safe to let go. The sense of the room surrendering together. The reminder that we are not alone.

If you want to see if the film is coming to a city near you, you can reference this website, which is updated frequently.

If we’re not coming to your city, it will be available worldwide through AppleTV+ (a streaming service available to anyone, on November 14th. We hope you have a watch party!)

Meg. I feel you through your words in ways that land directly on the open waters of my own heart. Thank you for staying. Thank you for skipping. Thank you for being on this side where we channel our grief into portals of light so we can high five our loved ones who have passed through to the place we can’t yet see. May you continue to feel it all.

"But let me tell you something about me: I will never leave the theater.

To be devastated in the dark reminds me I’m alive in the light."

YES!